Economics

Causality

Nov 2, 2022

If you’ve studied any economics before, you’ve probably heard the phrase “correlation isn’t causation”. It’s repeated enough times that it’s seen as somewhat of a truism. But what exactly does it mean and why is it important for us to understand why?

If you’re on the internet for long enough (which, let’s face it, everybody is) you probably see headlines like these pretty regularly:

If you take these headlines at face value, the sheer number of things you do daily that could cause your untimely death is seriously astounding. The reason you shouldn’t is that these studies examine correlations which are merely mathematical/statistical relationships between bits of data. In some sense, everything is correlated and with a data set big enough, you could find correlations between things that are causally unrelated. Here’s an example from my second-year econometrics course that made this distinction clear to me.

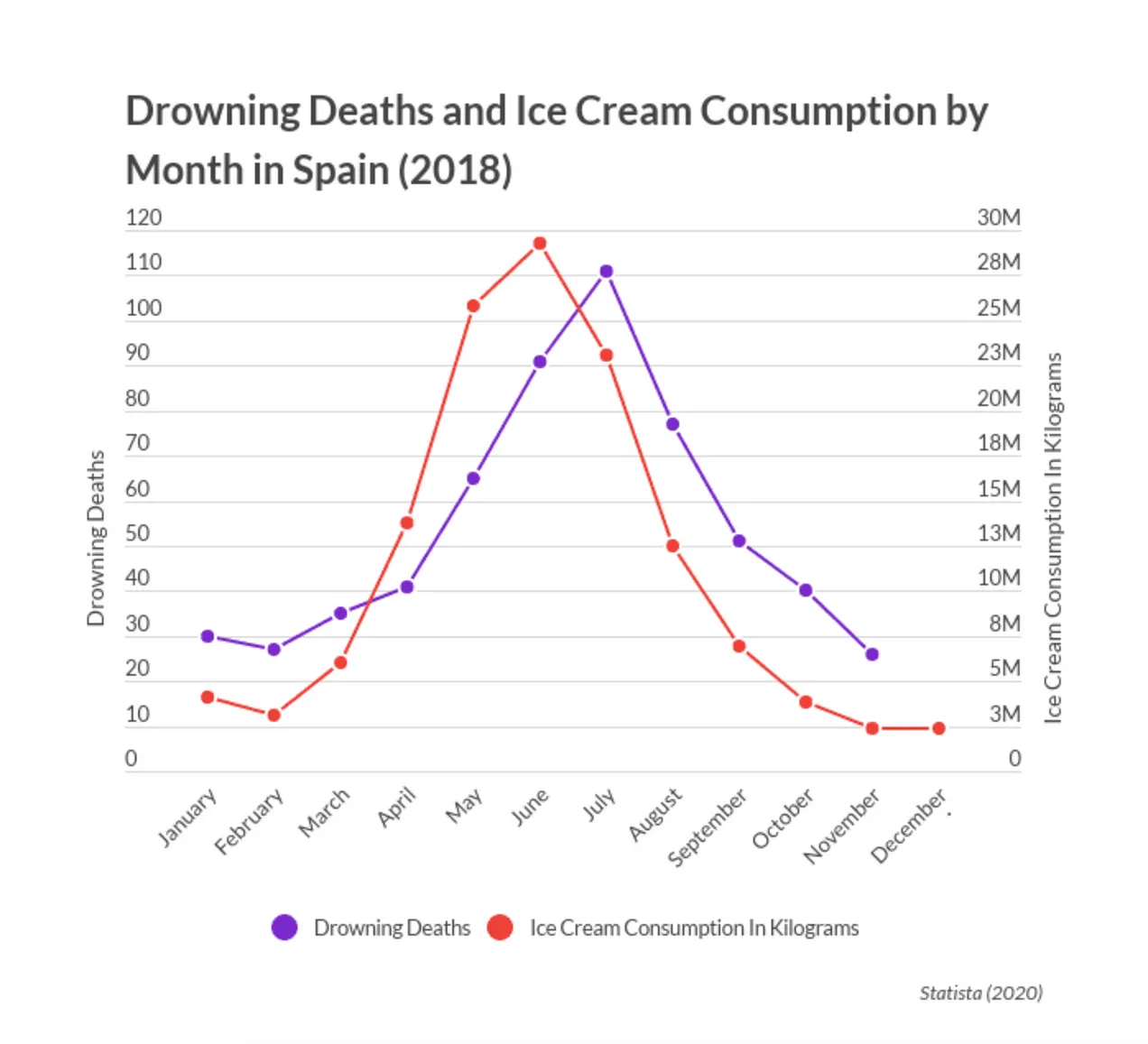

If you were to collect data on ice cream sales and the number of people who drowned, you would get a graph that looked like this:

At first glance, this seems bizarre. Of course, eating ice cream doesn’t cause people to drown. But if you look at the graph more closely, you’d observe a spike in ice cream consumption and drowning deaths between May and August which gives us a way to explain this weird correlation - the heat! During summer, people eat more ice cream but also swim more often and are, therefore, more likely to drown. So it’s not the case that eating ice cream causes drowning but rather that higher ice cream consumption and a higher number of drowning deaths happen at the same time of year (during summer). In this case, we say that the temperature is a ‘confounder’ because it masks the true nature of the causal relationship between our two variables of interest.

The fact that correlation doesn’t imply causation seems pretty obvious in cases like this. I highly doubt that if you went up to crowds of tourists in Ibiza enjoying ice cream by the beach on a hot summer day in June, shoved this graph in their faces and warned them of their impending doom you’d get anything other than a funny look. But science is full of correlations between variables where positing a causal relationship between them isn’t so absurd. Correlations between the behaviour of parents and their children are used in favour of the nurture assumption but the fact that parents and their children have similar genetics means that they may behave similarly anyway. Correlations between years of education and income are used to support the idea that spending on an expensive education almost guarantees your chance of a higher future income but maybe this is explained by the fact that people born into high-income families can afford more education and would have had a higher future income regardless of education.

Observing correlations is can be incredibly useful if you don’t care so much about causal relationships and just want to make predictions (eg: when making weather forecasts). The main takeaway here is that finding causal links between things in the world by observing data is much harder than we think and recognising this can help us make better decisions.